A Reflection on Boyz n the Hood

I had the opportunity to write a reflection on John Singleton’s cinematic masterpiece, Boyz n the Hood, last year in a Masters course in Urban Education. In his honor, I would like to share it with you.

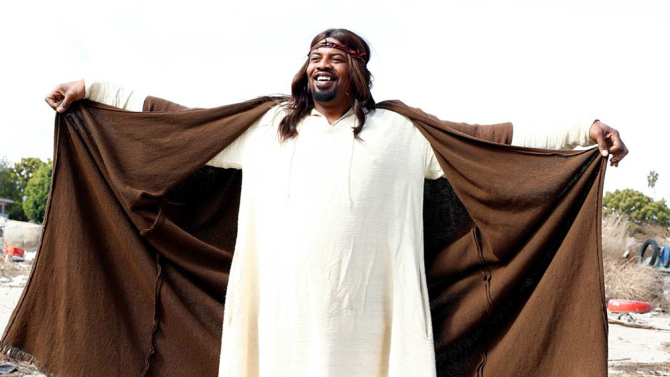

So many thoughts come to mind as I think about the movie Boyz n the Hood directed by John Singleton (1991). This is such an important movie on so many levels. One of the most influential Hip-Hop albums of the past decade, good kid, m.A.A.d. city by Kendrick Lamar (2012), basically retells the movie’s story in musical form, with Kendrick going as far as to say, “I’m like Tre, that’s Cuba Gooding,” on the album’s tenth track. Its lasting cultural impact can be attributed to the authenticity with which Singleton conveyed real issues affecting many poor and oppressed communities in the United States and around the world. His efforts resulted in him becoming the first African American director, and youngest person, to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director. As I watched the movie back, I could not help but feel like Ice Cube should have also received an Oscar nod for his portrayal of Doughboy. This movie would launch his film career, and inspire him to co-write Friday, another immensely important film. I remember reading in an interview years ago, that Cube’s motivation to write Friday came from a desire to show another side of the hood, more light-hearted and comedic than the portrayal in Boyz n the Hood. While Friday takes a more comedic approach, there is still a strong theme regarding the lasting effects of gun violence on poor and oppressed communities, as well as the powerful influence of fatherhood.

Doughboy’s character, Darrin Baker, is a tragic one. It is hard not to tear up as he brings his brother Ricky’s body into his mother’s home, after Ricky is shot and killed. In the midst of chaos, Darrin tries to console his mother and get Ricky’s son out of the room so he does not see the dead body. But this show of concern is only met with a projection of blame by his mother, who never loved him the way she loved Ricky. Neighborhood boys in the movie claim that this is because Ricky and Darrin have different fathers. The tears again begin to form as Doughboy reflects on his brother’s death the next morning, and as he then goes on to say that he knows his mother does not love him. Despite the vengeance he took on his brother’s killers the previous night, it is impossible not to feel empathy for Darrin in this moment, as his statement recalls the moment when we met him at the beginning of the movie and his mother was telling him that he is nothing and he will never be nothing. This is juxtaposed with the previous scene of Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne) telling his son Tre (Desi Arnez Hines II/Cuba Gooding Jr.) that he is a prince, and teaching him about responsibility. As an adult, Darrin leaves Tre’s stoop, and pours out liquor for his fallen brother; he then fades into nothing, just as his mother prophesied when he was a child, a boy forgotten by a society that, “... don't know, don't show, or don't care about what's going on in the hood.”

But the nuance with which Singleton and Cube portray Doughboy shows that he is so much more than nothing. Doughboy is interested in reading, philosophy, and religion. Doughboy recognizes the injustice in national news outlets covering instances of violence in other countries, and ignoring the violence that occurs in underprivileged neighborhoods in the United States. An injustice that left his brother nameless the day after he was murdered. Doughboy is a ferocious protector of his brother, despite the inequity his mother displays towards him. This protective nature is probably what gets him killed, as the film implies before it ends, a victim of the same retaliation with which Doughboy acted after his brother was killed. It is a miraculous cinematic feat that Singleton and Cube pull off, that as the credits start to roll you cannot help but cry for Darrin, after only minutes earlier seeing him brutally kill the three men who killed his brother. But, as Doughboy notes after leaving prison earlier in the film, he is not a criminal. He is a victim of circumstance, a victim of societal inequity, of his mother’s inequity, of his father’s absence.

As I listened to Doughboy reflecting with Tre on the stoop, and very matter-of-factly stating that everyone has to die, and he might be the one to get shot next, I thought about a specific girl in my class last year. She lost her older brother to gun violence the year before, when he was shot just a couple blocks away from the school. He was a student at the school at the time. She also lost her father to gun violence last year. He was my age; shot and killed at a party. I think of her often. I think about what it must be like to be thirteen years old, and, based on life experiences, to think that your life could be over very soon. People have difficulty dealing with midlife crises in their forties; imagine being in you teens with legitimate reason to believe that you may be at or past the midway point in your life. This past fall, around the one year anniversary of her brother’s death, this girl was experiencing a great deal of behavioral challenges. As we were problem-solving, a counselor suggested that it might be appropriate to place her in honors classes, and that the added academic challenge might motivate her to improve her behavior. The counselor and assistant principal had tried to put her into honors classes last year, but her mother denied her movement. This year they thought they would be able to convince her mom that it was a beneficial move for her daughter. We were able to successfully move her to honors classes, which has resulted in miraculous improvements. Not only is she excelling academically, but her behavior has completely turned around and she is forming more positive and productive friendships. My heart breaks for her often, though I do not let her see this. She has built up an exterior much like Doughboy’s, and does not respond well to implications that she is not strong and capable of handling herself. I am so excited that we have been able to present her with appropriately challenging academic tasks, which are helping to boost her skills and her esteem. As often as possible, I try to let her know how proud I am of her. I do not want her to fade away like Doughboy does at the end of Boyz n the Hood. On the contrary, she has already left a lasting impact on me, and I hope I can facilitate her achievement to make a lasting impact on a society which, 27 years after the release of Boyz n the Hood, still, “... don't know, don't show, or don't care about what's going on in the hood.”

This student’s story, and Doughboy’s story, show why it is imperative to address the societal inequity which exists in our nation’s education system. Tre succeeded in spite of a subpar schooling experience, due to the resolve and presence of his parents. But we cannot look to the exceptional instances of student success and say, “Look; it’s possible.” We must look at the Doughboys; at the students who do not have fathers like Furious; at the students who do not defy the odds. It is not fair to ask these students to “pull themselves up.” Rather, we have to improve the odds for them. What did the world lose when it lost Doughboy, long before his implied death, and more accurately when it labeled a child a criminal and arrested him as a ten year-old? What did the world lose when it lost his brother Ricky? What would the world lose if we lost the young girl in my class? What did the world lose when we lost her brother and her father? We cannot shy away from these questions, rather we must use them as purpose for confronting the inequitable situations that have been established. We must create an education system which facilitates promising futures for the Tres and the Doughboys of the world.